By Michael Neufeld

Edited by Natalie Grace Sipula

[4 minute read]

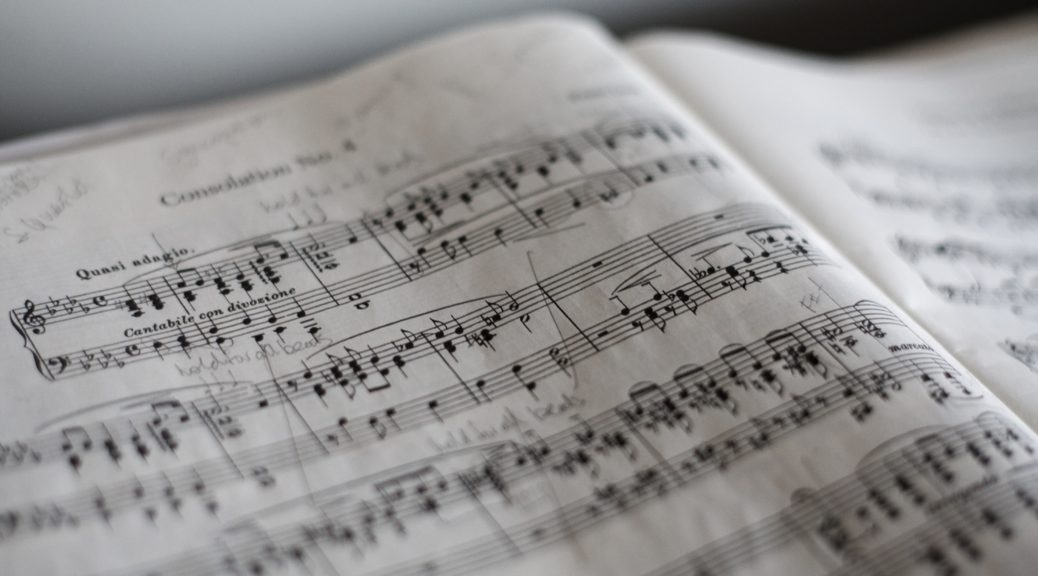

I get it, learning a language is difficult. Not only do you have to learn the vocabulary, grammar and syntax of a different language, but you also have to discover all of the nuances, idioms, and contexts for word usage so that the things that you say make sense and express meaning. Because learning an instrument holds many of the same challenges, music is often referred to as a language of its own. Not only must you spend time learning to play an instrument or sing, but you must learn to read and listen to it carefully to truly engage with it. There are multiple levels of meaning in music, and a lot of those levels are changed by the perception of the listener.

The main similarity between music as a language and actual spoken languages is that the content never changes. In the same way “a ball” in English is “una pelota” in Spanish, a D major chord may be called something different in a different culture. However, many cultures still recognize a ball as a round object used for playing games. In the same way, a D major chord still retains the same sound produced; it doesn’t change across cultures. Thus, when orchestras perform the works of Tchaikovsky, they will sound the same. Played with some level of variance due to the styles of each culture (think of it like speaking with an accent).

The sounds that are produced do not change much across cultures, so emotions and ideas can be universally translated. What I mean by this is, what sounds beautiful in America will often sound beautiful in Japan. What sounds bad in Germany will sound similarly bad in Mexico. A romantic song may still carry that romantic connotation in another context. A scary song can still be used to induce fear in other settings. This is the magic of music: it can carry such emotional weight across a variety of cultures and nations, and by doing so it transmits power, messages, and feelings where words cannot.

An example of this can be found in the popular J-Pop song, “夜に駆ける,” or translated to English, “Racing into the Night,” released at the end of 2019. I personally have a very small understanding of the Japanese language; although, I know enough to hear fragments of words or sentences, I cannot understand the entirety of a song without looking up translations. However, I can still feel the undeniable energy of a song, the compelling melodies in the vocalist and piano parts, and the emotional release during the breaks and key changes at the end. This song in particular has been on my mind since I discovered it for myself, due to its attention-grabbing qualities. Interestingly enough, this song was based on a Japanese short story by the name of “タナトスの誘惑,” or “Temptation of Thanatos.” Thanatos was the ancient Greek personification of non-violent death, likened to a god according to the mythology of the time. Here we can see how the art and ideas themselves have transcended cultures, both spatially and temporally.

Music differs between cultures because of the different ways each culture developed their unique sense of art over the course of the past thousands of years. Long ago, Europeans decided to quantify music into major and minor scales, resulting in theory developed because of specific works that utilized those set of rules. Likewise, Asian cultures that were separated from European influence came up with different sets of rules and different sounds, typically along the lines of what European theory at the time would call a “pentatonic scale.” Each country and its people developed its own unique sound, even though a couple of generalizations still hold true.

Recently, because of technological advancements music has had the opportunity to blend with other genres of music as well as transcend cultural differences. The most common example of this is American jazz, which was born in America from primarily African drums and harmonies, and similar fusions of genre and culture have impacted nearly every other major type of music in the early twentieth century. As such, music has begun a transition into a unique position where it contains bits and pieces from every place on Earth. It doesn’t require language to be processed by others who don’t speak it, yet it can still convey emotion through other aspects of itself. To me, music is one way that we are able to communicate with each other when words fail.

Featured image by Marius Masalar on Unsplash

Michael is a senior majoring in Jazz Studies at the Thornton School of Music. He lived in Fresno, California until moving to L.A. for college. In his free time, he can be found practicing the trombone, or playing video games. Michael has traveled all around North America, and he loves getting to know new people, listening to stories, and being a friend to others.