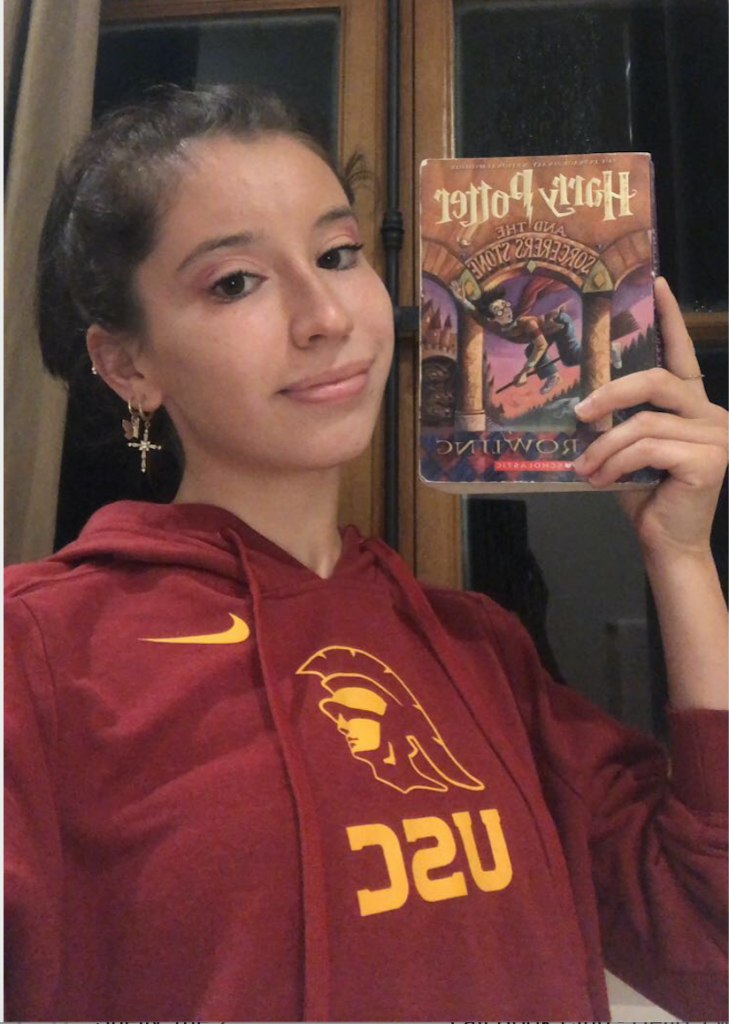

By Natalie Grace Sipula

[5 minute read]

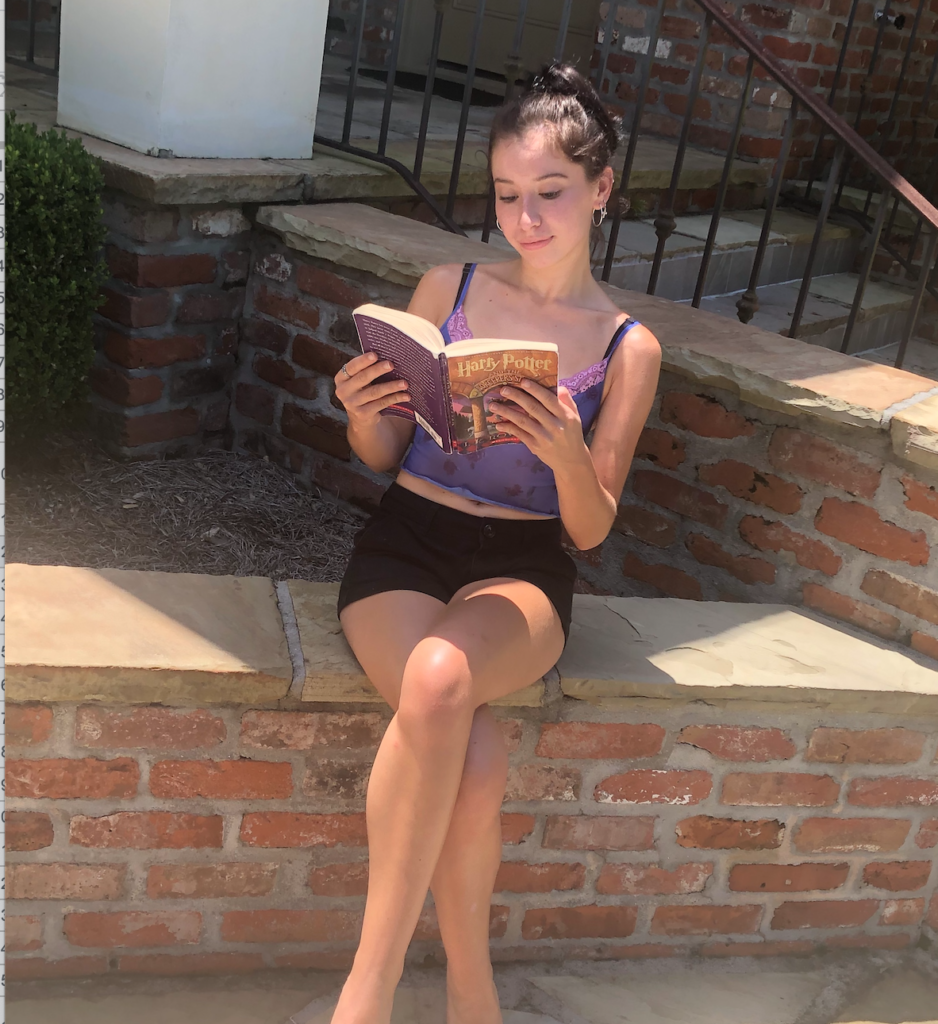

This summer I was a leader for the American Language Institute’s brand-new book club. I helped to lead discussions for this pilot program with international students, and the book we chose to read was Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. Like many other college-age individuals, both in America and around the world, Harry Potter was an integral part of my childhood. From the moment I picked up the first of those mysteriously thick volumes, I was entranced. The world of Harry Potter, in the eyes of a child, is often vivacious, all-consuming, and enigmatic-a land of opportunity for the child who sees part of themself in one of the multitude of characters or feels misunderstood.

I think that sometimes those of us who grew up with the Harry Potter series put it on a pedestal, carrying it in a place so deep in our hearts that it is hard to look past it’s many virtues to see some of it’s obvious flaws. Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone was chosen by the book club for an international audience because of its accessibility to a wide range of audience members, but that accessibility to many different age groups and backgrounds also suggests varying levels of complexity. Returning to the Harry Potter series in a discussion-based setting with older eyes revealed some interesting new layers to this book.

Initially, I noticed that triumph in the face of adversity was a recurring theme throughout the book. What becomes particularly important is the people who are successful in overcoming the obstacles set forth throughout the novel, and how they are categorized. Almost as soon as Harry steps foot onto the train taking him to Hogwarts, he learns of a rigid system which categorizes students into different Houses based on personal qualities or attributes. Despite the fact that Harry knows nothing about the wizarding world, he takes to heart everything that his new friend Ron says to him on the train about the virtues of Gryffindor and the downfalls of Slytherin. This blind assumption is never challenged (at least not for the duration of the first book in the series) but is instead supported by other students and professors. Everyone seems to be looking forward to the day when Slytherin is met with failure, whether that be in personal conflicts, the House Cup, or Quidditch tournaments. In a moment that has been pointed out for it’s ridiculousness multiple times from fans of the series, Headmaster Dumbledore, at the end of year feast, absurdly recalculates the House points once Harry, Ron, and Hermione recover the Sorcerer’s Stone to make it so that Slytherin conveniently loses the House Cup by a measly ten points.

To any child reading this, this may seem like the epitome of justness, wherein the stereotypical group of bullies are met with disapproval and failure at the hands of an all-powerful adult figure. But in actuality, this favoritism continues throughout the series, illustrating a tendency for the wizarding world to look down on a group of people with supposed traits that they perceive as threatening. While it is possible that J.K. Rowling was trying to create a world in which your success is based on personal virtue and strong morals, it is difficult to see how this idea can coexist alongside a system where children are categorized at the earliest point in their education and then judged and questioned for the rest of their lives based on that categorization.

Another aspect worth mentioning about the Harry Potter series is the interpretation of England which J.K. Rowling infuses into the magical world she has created. As an American preteen avidly reading the Harry Potter series, I did not have a particularly detailed idea of what the cultural landscape of the United Kingdom looked like. Returning to the series at nineteen years old with a greater understanding of UK culture, I see some vast differences between my new knowledge and the culture depicted in the Harry Potter world.

When we are first greeted by the presence of Hogwarts as observers of the nervous first years being transported in boats across the lake, we see a medieval-style castle, complete with towers, ghosts, suits of armor, and dungeons where the young wizards and witches take their potions class. The food they eat is old-fashioned: shepherd’s pie, treacle tart, and more. There seem to be few students of color in this world, but when they are mentioned, the reader is immediately tipped off by Rowling’s stereotyped names and descriptions-Dean Thomas being described as a black boy the first time he is mentioned, the only known Asian girl in the series being named Cho Chang, and the twins in Harry’s class of Indian heritage being almost indistinguishably characterized as Padma and Parvati Patil. In light of recent controversies of J.K. Rowling releasing transphobic statements via social media (which were met with outrage by Harry Potter stars Daniel Radcliffe and Emma Watson, among others), it is hard not to wonder whether those characters were included as a meager attempt to reflect the modern-day diversity of the UK or just a form of thinly shielded tokenism. As a young reader, especially one who is not originally from the UK, it is easy to overlook or misunderstand the Britain which Rowling portrays for us, but looking at the series with fresh eyes it becomes clear that this is a place that idealizes a medieval version of Europe that is disconnected from the thought and culture of the modern world and is predominately white.

I do not say these things to diminish the value that the Harry Potter series has added to the lives of many children and adults in countries across the world; Harry Potter and his magical friends will likely live on in our culture and imaginations for many generations to come. However, I encourage you to reread some books that you idealized and cherished as a child or at a past time in your life. Some of the most well-written books have the power to resonate with both a child and adult audience, and I think that the Harry Potter books, along with books such as The Chronicles of Narnia, The Lord of the Rings, The Phantom Tollbooth, and more, have staying power and cultural relevance because of that. That being said, some of those books come from a time far removed from the year 2020, and our young eyes reading them years ago may not have had the ability to read them with a discerning mind. As Ralph Waldo Emerson once said, “I cannot remember the books I’ve read any more than the meals I have eaten, even so, they have made me”. Take this time (perhaps the spare time you have in quarantine) to reflect back on the books and media that contributed to your growth from a young age.

If you are interested in reading and discussing books or short stories in a group setting, keep an eye out for the fall 2020 ALI Book Club schedule, which will be posted on our social media and website. Instagram: @usc_americanlanguageinstitute

Featured Image by Patrick Tomasso on Unsplash

Natalie Grace Sipula is a rising sophomore studying Philosophy, Politics, and Law with a Spanish minor and plans to pursue a career in criminal or immigration law. She is from Cleveland, OH and is a Presidential Scholar studying in Thematic Option. Natalie is an active member of Phi Alpha Delta (Director of Recruitment), QuestBridge Scholars (University Relations Chair), and Grupo Folklórico de USC. Growing up she was dedicated to theatre, including studying and performing at Cleveland Play House. She is a volunteer camp counselor with Mi Pueblo Culture Camp in Cleveland. Since arriving in Los Angeles she has enjoyed volunteering with Angel City Pit Bulls animal shelter and in her free time enjoys reading, writing, and going to the beach.